Sakhile&Me presents The Botswana Pavilion: Maš(w)i a Ditoro (tsa Rona), a group show featuring works by LegakwanaLeo Makgekgenene, Kim Karabo Makin, Thebe Phetogo, Thero Makepe and Sade Shoaloane. In the group's fourth iteration, the independent collective from Botswana have partnered with Sakhile&Me to present a show parallel to the 59th Venice Biennale. Maš(w)i a Ditoro (tsa Rona), which opens on the 25th of April 2022, brings together a richness of medium and material ranging from video, painting, sound and installation, photography and photomontage.

Taking its cue from this year's theme for the Venice Biennale, Maš(w)i a Ditoro (tsa Rona) translates specifically to, 'the Milk of our Dreams'. Where the theme is said to suggest life as constantly re-envisioned through the prism of the imagination, the Setswana translation presents a Botswana satellite that positions and presents the transnational workings of creatives from Botswana in Frankfurt, Germany — in The Botswana Pavilion's first iteration in Europe. The translation; 'The Milk of Our Dreams' brings into question what it means to share a collective idea or vision, as proposed by the Venice Biennale. Where 'The Milk of Dreams' exhibition as curated by Cecilia Alemani in Venice cites a re-envisioning of the imagination- a world where everyone can change, be transformed, become something or someone else- The Botswana Pavilion does so and brings into question notions of collectivity, nationhood, subjectivity, and the politics of belonging (elsewhere).

The satellite exhibition prompts one to contemplate the perceptions around and, perhaps, our sentiments towards nationality and nationhood. This, in the interest of creating transnational connections, whilst unpacking their 'creative identity' as a network of artists and art practitioners working both within and outside of Botswana. Participation at the Venice Biennale is an upper-crust endeavour where a selection of artists are chosen to represent their country at their respective pavilions in Venice and present their works. Botswana has never presented a national pavilion in Venice, prompting this group of emerging contemporary artists and makers from Botswana to take it upon themselves to actively interrogate Botswana's creative identity, collectively, and across national and international borders, engaging counter-narratives and debates around the nationalistic nature of occasions such as biennales.

In relation to the title of the exhibition — Maš(w)i a Ditoro (tsa Rona), the idea of national pavilions at the Venice Biennale and the nationalities represented thereof, Botswana occupies a non-existent space at the Biennale. The satellite exhibition in Frankfurt interrogates this vacuous space, and is not necessarily a replacement to that lack of participation but rather exists in the gap and absence of an 'official' state sanctioned participation in a divergent manner. Part of the programming sees a number of virtual aspects that tie back to Botswana, bringing the exhibition full circle, to, in many ways the place of its genesis.

These artists have framed their individual practices in the forms, symbols, and narratives of Setswana culture, indiscriminate of time and place. These are used as markers of authenticity in their engagement with global Modernism. They generate national narratives for and of Botswana, and of a modern and contemporary African art that intersects with global discourses. There is an inherent awkwardness between art and nationalism as contemporary art is a practice that is subversive, critical, and characteristically challenges the mainstream ideas and conservative thoughts that nationalism depends upon. Cultural critic Homi Bhabha once noted that the idea of the nation is a narrative construct that organises how people relate to a political and cultural location in time and place. According to Bhabha " nations, like narratives, lose their origin in the myths of time and only fully realise their horizons in their mind's eye." Bhabha here points to the mythical nature of national narratives, which often stitch together discordant ideas about the best ideals of the state and retrospectively reconfigure these as national histories.

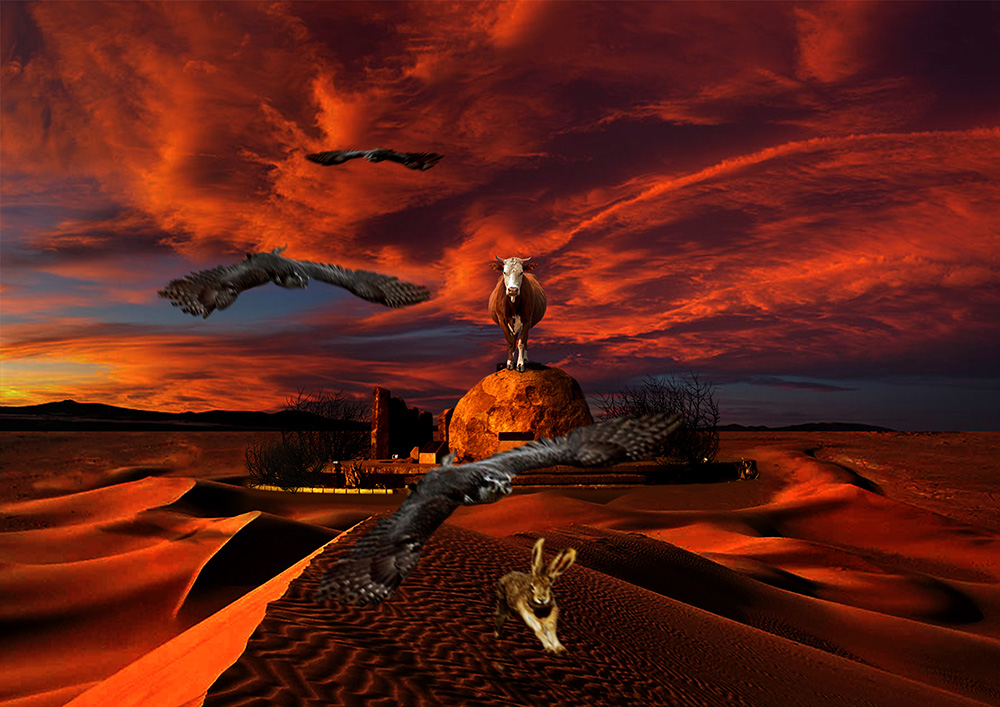

This is central to the work of these artists, seen particularly in LegakwanaLeo Makgekgenene's photomontage series. The works delve into Botswana's national narrative (and origin story), past, present, future, real life and virtual/digital folklore and use monuments and memorialisation to explore myth, and the gamut of Setswana mainane, diane, maele (fables, proverbs, idioms) etc. Makgekgenene, through their photomontages, has set about to deflate the false sense of stability and well-being demonstrated in vacuous public monuments. This series interrogates two of Botswana's main landmarks, the Three Dikgosi Monument and the Sir Seretse Khama statue. The Three Dikgosi statue was erected in 2005 and memorialises Khama III of the Bangwato, Sebele I of the Bakwena, and Bathoen I of the Bangwaketse who are known to have been instrumental in securing Botswana's protectorateship status and independence from the British thereafter. Digagabi (2018), the first interaction with the site, draws on oral and folklore culture, using the urban lore surrounding the southern African rock agam or 'bloukop' lizard to trouble the reading of these figures and their place in our shared consciousness. The lizard is generally feared and respected, and in local Setswana lore, carries a confusing reputation- known to spit and change one's gender, look in one's eyes and cause paralysis, shapeshift, talk, etc. Likening this mystification to the somewhat unsubstantiated reverence the legacy of the Three Chiefs carry for Batswana.

Le bipa dimpa ka mabele (2021) and Ke utlwile ga e tshwane le ke bone ka matlho (2022) were made in following years. Le bipa dimpa ka mabele, adapts a proverb that means to conceal a secret and creates a visual translation specific to the site - implying that the figures and this particular part of Setswana heritage, harbours secrets. Ke utlwile ga e tshwane le ke bone ka matlho, " I heard is not the same as I have seen it with my eyes," again refers to the official independence narrative. Opposing accounts from people who were privy at the time have been dismissed in favour of the dominant narrative, writers and political analysts have discussed the indiscrepancies at length and yet the narrative persists, unchanged. The Three Wise Monkeys embodies the proverb see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil, which suggests that some things should be 'tuned out' of one's perception in favour of immaculacy or harmony.

Ditlamorago (2022) are 'the things that come after/follow-consequences', this work considers the 'coming round' motion of Botswana's Independence Day and decades-after celebrations of the basis on which the country was formed. The piece takes into consideration the public image that was formed and that then had to be maintained (and is carefully tended to almost 60 years later) that is the root of many systemic and ethos concerns today. Botswana was founded as a resource-based economy, relying on cattle farming, agriculture and the presence of diamonds to build its wealth and respectability. In 2016, with the influence of the current President, the move toward a knowledge based economy began. The core shift and ideological turn around was inevitable and one of many for a country that achieved independence without being motivated by aspirations to overhaul certain doctrines or by a sense of Revolution. In relation to the title of the exhibition Maš(w)i a Ditoro (tsa Rona) and the idea of national pavilions at the Venice Biennale or of our particular nationality, these works question the foundation of Botswana's national identity, disorienting the history through folklore and proverbial tropes. These works look at the current state of the nation from the viewpoint of its conception and articulates the nervous distress of disenchantment as stills from a fever dream.

The Botswana Pavilion demonstrates that they are aware that the stories we tell each other about our national belonging and being constitute the nation. Aware that these stories change over time, warp in different places and remain disputable. This narrative process involves the shaping of collective memories and the works in this exhibition allow the viewer to witness and analyse the intertwining of discursive, cultural and national constructs, aesthetic value, and the distribution of power that led to the make-up of Botswana and its cultural markers.

Kim Karabo Makin breaks down racial compositions in Colour Theory (2020) and attempts to define the transnational space within which the artist exists, it is a comment on race as a social construct. Colour Theory translates the world of colour to a racialized palette of assorted 'nude' pantyhose. To reimagine the world of colour within this scale, is to reimagine the artist's sense of self within South Africa's racialised landscape. Exploring her identity as racialised by offering variations of the racial spectrum, the artist makes reference to the painterly colour wheel and contemplates whether the variations of hues are in fact, variations of the same colour, or instead, whether each shade represents an individualised colour in its own right. By extension proposing similar questions about racial categorisation and associated social dynamics. Colour Theory (2020) introduces an exploration of the circular as a social symbol of identity and sense of self and unpacks what constitutes 'nude' (as a racialized motif in the work). The set of works was made using panthose from local stores which only stock 'nude' stockings in four basic colours: Bare Beige, Beach Bronze, Mexican Silver, and Blackmail. The colour wheel as we know it, at the most basic level, features three primary and three secondary colours. This leads one to consider the extent to which the artist may explore colour theory, following or disobeying racialised colour distinction in their context.

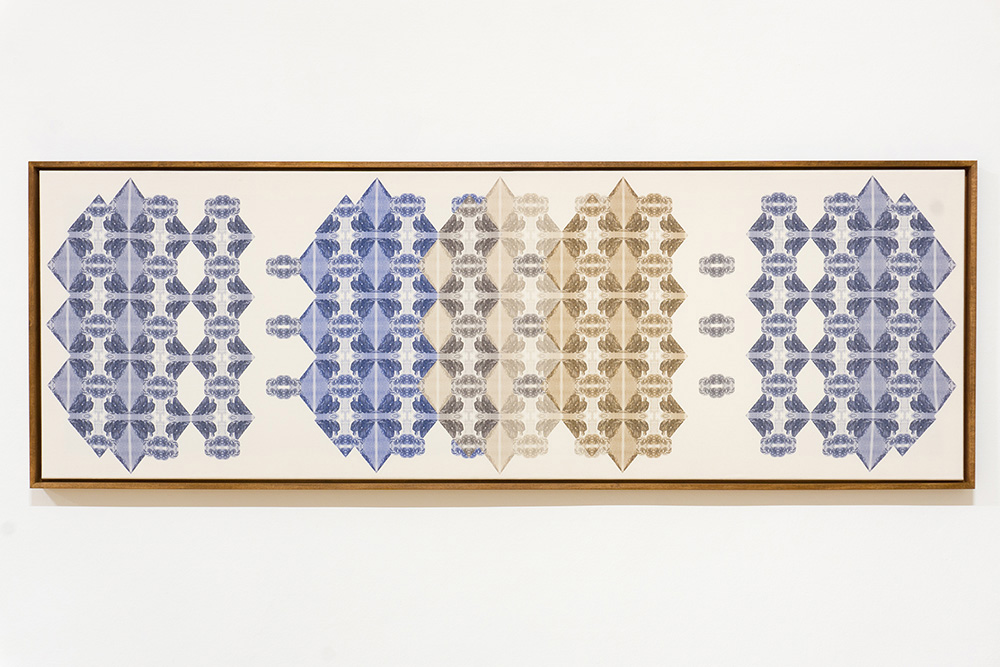

Botala jwa Botswana (2020) features a repeated pattern design that borrows and extends from the face of the one-hundred Botswana Pula note. This significantly includes a depiction of the Three Dikgosi (Chiefs), who are monumentalised as fathers of the nation for their role in the Republic of Botswana's grand narrative. Where the use of money seems to denote an aspect of cultural currency, the varied pattern of geometric triangles and circles in Botala jwa Botswana also seem to interestingly resemble the design of Botswana's traditional dress, leteisi. By intricately weaving the history of the Three Chiefs with the cultural value of particular geometric patterns and traditional dress, Botala jwa Botswana unpacks the layers of societal make-up and fabric based on the artist's lived experience of daily life in Botswana. Therefore, Botala jwa Botswana critically engages the colour blue with respect to a particular sense of subjective nationhood. The title investigates the colour blue as subjective in the context of Botswana, with a critical look at the cultural value and meaning of botala (blue/green). Interestingly, in Setswana, botala may be used interchangeably to denote the colour blue (as in the phrase botala jwa loapi, which directly translates to 'the blue of the sky'), or otherwise green (specifically known as botala jwa matlhare or ditlhare, which specifically refers to the colour of the leaves/trees, or arguably, the 'blue' of the leaves/ trees). However, both colours may be referred to simply as botala.

Defining nationhood has always been tricky; it is impossible to reduce one's " nationality" to a single dimension, and neither subjective nor objective definitions are satisfactory, as both of these constructs are constantly in flux, governed by ambiguity and subject to the elements of myth-making, and social and cultural engineering. In today's multicultural world, it would be wearisome to attempt to formulate an objective criteria for nationhood—since identity, place and sense of belonging are fluid concepts, subjectivity in this instance becomes a powerful tool.

Identity, personal and familial history is evinced in the photographic work of Thero Makepe. Makepe looks at the confluence of personal and collective history as both needing the work of active engagement in order to 'uncover'. The artist performs in the footsteps of those that came before him, he examines how traditions and ways of being are established, and suggests that identities both personal and national are compositional. In Monna Wa Mmino III (2020) (man of music, in English) is a re-enactment photograph of the artist taken at Robben Island, where Makepe's great-granduncle, Zephania Mothopeng, was imprisoned twice from 1964 to 1967 and again from 1979 to 1989 as a political activist. As a former teacher and school choir conductor, "Uncle Zeph" , as he was affectionately known, had chosen to oppose the Bantu Education Act under the apartheid system in 1953. After losing his teaching position, he became a political activist and prominent member of the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC). Eventually, he became the second president of the party in 1986 while still imprisoned on Robben Island. At the same time that his Uncle Zeph had chosen to become an activist who had dedicated his life to dismantling the racist and oppressive system of Apartheid, the artist's maternal grandfather, Hippolytus Mothopeng, had fled South Africa to Botswana in 1958 to seek a better life with aspirations of becoming middle class. During the 1960s and 70s, along with other South African immigrants and exiles, his grandfather formed two jazz bands, the Metronome Swing Orchestra and the Scarers, who performed regularly in Botswana. Although he performed as a hobbyist while still maintaining office jobs to provide for his family, his dying wish was for one of his children or grandchildren to become a musician. In this same time period, the artist's grandfather's cousin and Uncle Zeph's son, John Mothopeng, was also a practising musician. They founded the influential jazz band Batsumi in 1972 and later on funk, rock, and roll inspired band Marumo in 1982.

In Monna Wa Mmino III (2020), the aim was to combine the two legacies of musicality and activism of his maternal family by performing with his grandfather's trombone in the attire that he would have worn during his performances at the Robben Island lime quarry. The artist subsequently attempts to reflect on what these two legacies mean for him in this present day. The title, Monna Wa Mmino, is a title taken from a 2009 drama television series with the same name, based on Mike Masote- Zephania Mothopeng's son-in-law, who realized his dream to form the first 'all black orchestra' during the apartheid years in South Africa and was the founder of the Soweto String Quartet.

Robben Island University (2020) is a documentary photograph taken at a cave at the Robben Island lime quarry, where political prisoners were forced to mine limestones. During this time and through this manual labour, prisoners on the island discussed different views, philosophies, and ideologies. As a result, it became a place of organic knowledge. Makepe's photographs and to some extent Makin's works point to problematic aspects of myopic nationalism or the idea of a single national identity. By contrasting snippets of life in Botswana with scenes and glimpses of life intertwined with their experiences in South Africa the artists, and particularly Makin, trouble one's ability to imagine a safe or tidy interpretation of identity, especially across cultural and historical contexts. They, instead, compel the viewer to imagine a fluxional interpretation of identity that could bear scrutiny in today's condensed world.

Dreams, hallucinations, and visualisations are a focal point of Sade Shoalane's work, a seven-part video montage, titled Mosamo (2022). Mosamo in Setswana is a pillow that you put your head on when you go to sleep. This work explores the idea that we are most vulnerable when we sleep and that, though dreaming and visualisation can be deemed as vulnerable states, they can also be seen as states that facilitate transformation. Dreams of disruption, revelation, critique, restoration, spirited schemes, regeneration and of unprecedented being. Furthermore, the work interrogates the idea of aesthetics; the work was entirely shot on an android , subsequently, using a 'low quality' cell phone to resist the motion of new technologies as evidence of progress, advancement or as aspirational.

The work is segmented and layered and in each segment, the artist contends with un/conscious sleep, the visuals as weaved together, driven by experimentation and a multidisciplinary approach to their work. Using found objects, fabric and textiles, the latter were subsequently set aflame to symbolise the transformative nature of fire and its transmutative powers in what the artist describes as a " cathartic process."

In certain moments, the video captures various orbs that one could say represent the different elements of nature. The golden hues that represent the fire element as discussed above, that transmutes, the blues that symbolise water and the process of rain-making or " rain-asking" as the artist refers to it. And perhaps the green that refers to the nurturing aspect of go roka pula – rain asking in Setswana that is, pula e dirilweng (rain that has been made). The video is accompanied by narrations and dream recollections of the artist that bring the viewer/listener into this dreamscape that the artist has projected.

The work also centres African spirituality and environmentalism- addressing historical and cultural 'over-writing' through creative re-indigenisation. The symbolism in the work sees and represents fire and water as transformative, exploring not 'who we are' but rather 'what we can become' and in this way, frames re-indigenising as an ideal for growth/development.

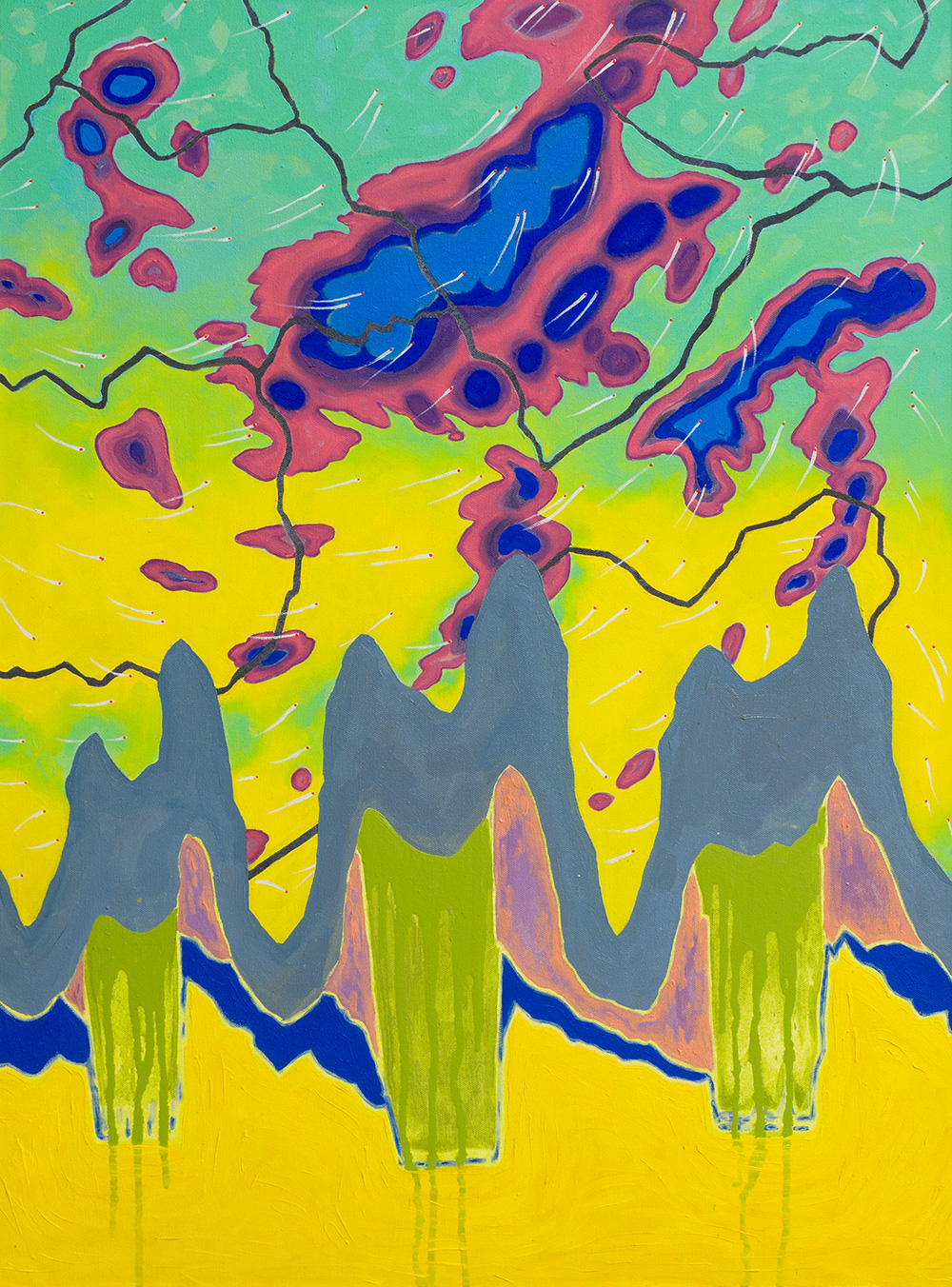

Artists employ different modes of communication — didactic, evocative, commemorative—to birthe their ideas. We can appreciate these modes in the landscapes of Thebe Phetogo, the photographic compositions of Makgekgene and Makepe, and in the video work of Sade Shoalane who seeks to give shape and meaning to the cultural ideals of authenticity. Landscape in Phetogo's work Untitled (Lowe 1) (2021) and Untitled (Lowe 2) (2021), is informed primarily by using existing systems of representation: cartography, infographic, colour systems and pseudo-landscapes. As these systems can tend to be inaccurate in terms of direct representation, these works offer a distortion of the subject matter at hand. The imagined landscapes contend with Folkloric mythology and Botswana's origin story of Lowe, where it is believed to be the site where the first human being emerged. The works explore the history of Botswana, both political and mythological, through the lore of the caves of Lowe, and other figures of divinity such as Matsieng, and Tintibane who are associated with these caves and footprints which are central to Tswana religious beliefs and practice(s).

Taking into consideration the lack of a recorded art history in Botswana, in the western traditional sense that is, Phetogo's paintings take as a departure point the cave paintings that are littered around the country as an art historical account. However, leaning towards abstraction, the work is a meditative project for both the artist and viewer, as the "thing" is not represented as is, but rather it is abstracted and employs less obvious modes of representation for this kind of work.

In Untitled (Lowe I), Phetogo uses those aforementioned existing systems of representation. This mode of working is sustained in the second work Untitled (Lowe II), where the artist borrows from the lexicon of weather maps as a predictor used for forecasting . This system then becomes a metaphor for pula as part of the Setswana lexicon. The infrared colours so vividly employed speak to an artificial colour/lighting relating to the green screen and the rainbow scale.

The indirect representation and the inaccuracy in terms of direct representation of the Lowe lore is a key, although it might seem paradoxical, for what that information is for. It stands for an unknowing, holding something back, a distortion, a false kind of system, usually a colour blind system of something that might be true but is considered myth such as Botswana's post-independence narrative.

The folkloric mythology and origin story of Lowe is the foundational myth of Botswana . The prehistoric origin narrative gives birth to a newer origin story, the Botswana political post-independence narrative. There is an element of the past that is interacting with the present in Phetogo's work. Whilst the work does not offer a naturalistic depiction of Lowe or direct critique of the post-independence narrative that some of the other works in the show so thoroughly engage, the work also does not seek to resolve, nor is it predictive but the artist sees it as a draft of something that is yet to come.

The Botswana Pavilion has looked to imagined versions of the(ir) pasts to express nationalistic sentiments, cutting through layers of imposed or fictitious ideas of 'Motswananess' to reach what they deem to be their "authentic" Setswana identity. The collective, through their work is shaping the course of an art form, particular to Botswana, that is in no way limited to the physical or national boundaries of Botswana and that works towards an expression of a nation that shares its historical timelines with many neighbouring countries. This mode of working is neither national nor international but is inherently transnational- curated around common regional concerns, the exhibition eschews the very idea of borders and inwardness.

Artists are not merely a consequence of but can be, the cause of social influences. The possibility of the latter for The Botswana Pavilion becomes an extension of their work as a collective- it would be meaningful to witness what they could mean for contemporary arts in Botswana. Currently unreliant on, though unopposed to the support or patronage of the state, the group, through residencies, grants, curated and travelling shows such as this one, art festivals and other fringe events, has blossomed . These, in turn, have encouraged an atmosphere of collaboration, exchange and critique that is central to the collective's aims. Through their work The Botswana Pavilion unmasks methodologies, modes of production, being and knowledge and authoritative terms/forms of political authority in relation to artistic practice. Collectivity becomes a space for refusal, a rejection of the terms and conditions given to them as artists, The Botswana Pavilion becomes a tool that is generative in creating a platform for the art/ists to thrive in and out of Botswana.

Text by Nikita Keogotsitse, co-edited by The Botswana Pavilion

Nikita Keogotsitse (b. Serowe, Botswana) is an interdependent art practitioner currently based in Johannesburg. Her interests are sprawling, and include ways of knowing, and epistemic injustices, as they relate to issues of gender, race, and representation. Her occupation(s) include writing, curatorial practice, and art-making, which are fuelled by a confluence of the metaphysical, the esoteric, African cosmology, and spiritual knowledge systems as a way to theorise, think with, through, and about art and visual practices.